The Victorians were

terrific collectors of both the animate and the inanimate, often indiscriminately

and always excited by the rare and exotic. Each variety of collector had its

name, usually confected out of school Latin or Greek: there were the butterfly

collectors (lepidopterists), stamp collectors (philatelists), coin collectors

(numismatists), inscription hunters (epigraphers), book fiends (bibliophiles),

the magpie collectors of junk in general (antiquaries or antiquarians). The leading figures in each field were often obsessives

who neglected others and themselves – their personal hygiene could not be

relied upon – and, as in the notorious case of the bibliophile Sir Thomas

Phillips, they could rack up very large debts in pursuit of their hobbies.

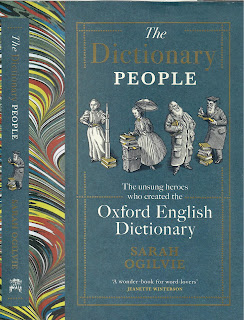

As part of this cast of

thousands there were also the word collectors - the logophiles, philologists,

and lexicographers - who form the subject matter of Sarah Ogilvie’s wonderfully

researched, beautifully conceived and well-executed

book in which she narrates the story of how the Oxford English Dictionary (OED)

was created in the period preceding the First World War when James Murray was

its long-term editor.

I have my doubts about

dictionaries and have never been a great user let alone reader. I possessed a

Shorter OED as an undergraduate but don’t have one now.

The Victorian

dictionary-makers claimed inspiration from the latest movements in German

philology which to the Victorians was really one word, Germanphilology. Ogilvie

alludes to Germanphilology but does not really tell us what its achievements

were or why we should be concerned with them.

In dictionaries like the

OED the living and the dead - words we might use and words we never will - are

side by side, the living ones are supposedly illuminated by their history. Their

ancestors are to be found in written texts - there was no sound recording of

the past available to the Victorians - though the descendant language exists,

of course, in both speech and writing. The heart of the lexicographer’s work is

the tracking of the way words have been used through time, how their meanings

have changed and expanded..

The OED was built very

largely on the voluntary efforts of thousands of readers who read not for

pleasure but to locate occurrences of words in print which could be dated from the

publication in which they occurred and which fairly clearly indicated the sense

in which they were being used. Just as stamp collectors hunt for the earliest

date on which a Penny Black was used so the OEDs readers tried to push back in

time the first occurrence in print of a word which – well, it may now be

completely obsolete just like the Penny Black. There are some complications

created by the fact that spellings change which are a small part of the

problems around treating a word which was used then as the ancestor of a word

which is used now.

In the case of what came

to be called dialects it is almost exclusively in spoken form that they exist

or existed (that’s what got them called dialects in the first place) and before

the invention of sound recording they were hard to study unless some writer

decided to try their hand at that excruciating genre known as the dialect novel.

It was the institutionalised creation of “the English language” which created the

dialects in the sense we now understand them.

But though a living

language has the past in its DNA it has its meanings in the present, in the

current inter-relations of its words as part of active and always mobile

semantic fields many of them culturally reflected upon and policed to ensure

that we get it right and, among other things, do not cause offence. It is a

headache for the Office of Standards that nowadays so many Advanced Warnings are announced in bold letters and so many claims refuted daily in the newspapers

Ogilvie discusses the

headaches which sexual words and swear words - she has nothing to say about

blasphemous words - caused the Victorian makers of the OED. Alongside what it

included there existed all that it excluded; despite the aspirations of its

makers to achieve inclusivity. The OED belonged to the cancel culture of its

time if only because Oxford University Press believed itself - as it still does

- a guardian of morals. (Surprisingly, perhaps, Ogilvie’s book is not published

by OUP but under the Chatto & Windus imprint of Penguin/Random House. But neither OUP or the University of Oxford come out of the story she tells in a particularly favourable light).

Propriety lasted well

past the Victorian era: Lesbianism did not appear in the dictionary

until 1976 before which time the entry for “Lesbian: of or pertaining to

the island of Lesbos” was designed to enlighten no one (see Ogilvie page 226). The

only concession to modernity was to provide an entry in English, not the Latin

once used to keep knowledge of sexual matters away from the lower orders.

Of course, there might

sometimes be a good reason for keeping a word out:

“Blandford wrote to him [James

Murray] that aphrodisiomania, an abnormal enthusiasm for sexual pleasure,

was a word coined by an Italian professor and ‘doubtful whether it can rank as

English’. (Murray did not put it in the Dictionary).” (page 161). After all,

since there was no abnormal enthusiasm for sexual pleasure anywhere in

Victorian England, there was no need for a word anyway.

The OED fosters an

illusion that there is such a thing as “the English language” which is more

than a social construct or matter of belief and aspiration. In relation to

vocabulary the longer you make the vocabulary list the more implausible it is to

suppose that what you are cataloguing is “a language”. What you are really

doing is attempting a cultural encyclopaedia from small fragments and with no

clear boundaries. Ogilvie notes many cases where a word entered into the OED

has just one known use (often in a novel or medical textbook) and seems

to be unperturbed by that. But to admit words with one known use is really to

admit that you are creating a bricabrac shop, a cabinet of curiosities mostly

covered in dust.

If there was such a thing

as “the English language” at the level of words it would be a fairly simple

matter to decide if a word is in it or not. In printed text the presence of a word

thought foreign is often indicated by use of italics. Would that it were that

simple; loan words cause headaches for the typesetter: is “ennui” an English

word and therefore not needing italic? Does

a person’s possession of a “je ne sais quoi” require italic? (See on this site

my review of Richard Scholar’s Émigrés on 28 October 2020).

If that is not enough,

consider the formation of words by analogy, a favourite of Germanphilologists and something which now excessively happens in

the case of -philes and -phobes. I doubt that anyone would

challenge the status of “Francophile” as a current English word nor give it italics.

But if I am a lover of Australia can I call myself as Australophile ? Or

just a lover of Australia? What gets a word into a (living) language is not

that some obscure or awkward squad author invents it for a one-off occasion of

use but that in some sense it catches on. Clearly, -phobes catch on more

easily than -philes – that tells you a lot about our culture, I suspect.

This morning, I read that Dmitry Peskov has been talking about Russophobia.

Smart move; no one wants to be thought a -phobe.

But because we understand

the formation of words by analogy we don’t need a dictionary to know what

someone means when they declare themselves an Australophile or Christophobe. It

makes no sense to try to create a dictionary out of an indefinitely long list of

personal idiosyncracies, including those favoured by the forgotten inventors of

forgotten wheezes (see Ogilvie’s chapter on “Glossotypists”). This is the stuff

of antiquarianism not of authoritative language guides.

I guess that out there are

various answers to the question, How big a vocabulary do you need before you

can be counted a fluent speaker or writer of language X? A few hundred? A

couple of thousand? The contents of the Shorter version of the Longer

dictionary? You can be perfectly fluent in English without knowing what’s in the

OED though if you want to write like James Joyce or Vladimir Nabokov it will

come in helpful when you want to bamboozle. Most often we identify non-native

speakers not by their lack of vocabulary – which may be larger than our own –

but by their accent which we can immediately and unreflectively identify as

foreign without having any knowledge at all of phonetics, phonology or prosody.

And in writing, it is small syntactic oddities not misuses of words which give

the game away.

Whatever the English

language might be (see footnote for my own answer), one might say that it is at least

as much about phonetics, phonology, prosody and syntax as it is about words and

their meanings.

Ogilvie

records a regret which James Murray had towards the end of his life as the OEDs

editor in chief: “If he had his time again, he said that he would have directed

his Readers [ those who sought out quotations for the OED] differently, with

the instructions, ‘Take out quotations for all words that do not strike

you as rare, peculiar, or peculiarly used’”

But looking for the rare

is exactly what all Victorian collectors/hobbyists did: they looked for rare

butterflies (until they rendered them extinct), rare stamps, and exotic curios.

They were uninterested in the ordinary, the everyday, things as common as

ditchwater. They often went to great lengths to track down the rare and the

exotic and that is what the makers of the OED did too. Like many or most

collectors, they were attracted by escapes from everyday life..

Note

Trevor Pateman, “What is English if Not a Language?”

in J. D. Johansen and H. Sonne, editors, Pragmatics

and Linguistics. Festschrift for Jacob L Mey, Odense University Press 1986,

pages 137-40.